Inclusive Design – Design Thinking – Hardware

When designing for the disabled, fit is the finish

A one-size-fits-one toolkit for designing inclusive hardware

Today, we’re releasing a new hardware toolkit to help you design products that give agency to the disabled community. Years ago, we started our inclusive design practice to identify and eliminate mismatches that create barriers for disabled people. As part of this effort, fit emerged as an important concept. We don’t believe in one-size-fits-all—instead, we strive for one-size-fits-one.

As we continued our inclusive design journey, the flexibility of software inspired us. Designers can tailor digital experiences to fit people with disabilities, but hardware products have a physical form and are rarely as fluid. By implementing our inclusive design practices, we aspired to create adjustable, augmentable forms that meet individual needs. This meant we needed to develop a toolkit to help designers produce truly inclusive hardware. Devices need to support experiences that intertwine the digital and physical. Therefore, our approach to hardware is to create flexible systems through the lens of our new toolkit, Devices + Accessories + Augmentations.

If accessibility is the solution, then disability is the opportunity. Disability is complex, so we must design flexible solutions.

Devices + Accessories + Augmentations

People interact with computers in infinite ways, across infinite contexts and functions of human diversity. Tailoring adaptive systems of input and output can significantly improve the experience for a diverse group of people with disabilities. Device design should strive to find a balance of perceivability, operability, and understandability. That means interface components should be easily perceivable or detectable. People should be able to effectively operate a product without having to align with specific input methods like mouse-only navigation. Content has to be easy to understand and straightforward, avoiding any jargon or complex terminology. These principles guide designers and developers to create experiences that are usable, informative, and welcoming to everyone, regardless of their abilities.

To identify the diversity of needs, we partnered with disabled communities. Where necessary, we made thoughtful and intentional compromises to meet as many of these needs as possible. A robust ecosystem of devices, accessories, and augmentations gives people unlimited possibilities for creating a system that fits their needs. Through research, empathy, co-designing, and iteration, we’ve developed the following toolkit to design devices for diverse disabilities.

Awareness is essential

People with disabilities are the true experts on the barriers they face. Yet they might not always be aware of the solutions or designs that can help overcome or eliminate those barriers.

Many people remain unaware of devices designed for people with disabilities. Raising awareness of products tailored to disabled people is as crucial as creating the products in the first place. Support materials should not only include instructions and tips but also feature demonstrations by disabled people so others can see someone like them succeeding with the device.

It is essential to foster communities where we can share and curate knowledge for the benefit of all.

Adjustments are augmentation

Ergonomics began during World War II, adapting equipment design to human capabilities for better efficiency and safety. Products designed to be adjusted provide built-in augmentation. Minor adjustments make a product fit you, and the better the fit, the more usable it is.

People vary in size, shape, preference, and ability. Adjustability is crucial to cater to these differences, fostering comfort, productivity, and safety, making a device more operatable. For example, when you change the tension of thumbsticks on an Xbox Elite Controller 2, you are doing these adjustments to enhance your precision.

Ensure wide-ranging adjustability to encompass diverse disabilities. To echo renowned disabled speaker Todd Stabelfeldt: sometimes, mere millimeters distinguish accessibility from inaccessibility.

Configuration is augmentation

Contemporary products blend physical and digital experiences. Personalization emerges through configuration. Accessibility can be personalization that accommodates human diversity. Some disability advocates, like Aderyn Thompson, believe that all settings, digital or physical, are accessibility settings.

Configuring product functionality, like with Microsoft Adaptive Accessories, brings efficiency and flexibility to different scenarios and long-term usefulness as needs change. For example, the Microsoft Adaptive Hub lets you customize not just button functions, but also how long you press a button, allowing different actions based on press timing.

Finding the right balance in options is essential. Perceivable and understandable configuration options should enhance functionality for diverse disabilities without overwhelming people with too many settings.

Physical augmentation is not required

In certain cases, purpose-built devices and accessories offer the best solution, without the need for additional augmentation.

The HumanWare Brailliant BI 20X, a refreshable braille display accessory, exemplifies this approach. For many, it’s so empowering that it’s more important than the device it’s paired with. This purpose-built device centers the needs of disabled people by default, without additional augmentation.

Sophisticated and straightforward approaches

Disability communities have a rich history of augmenting objects to fit their needs, driving accessibility through innovation. Designers should follow their lead with a focus on quality modifications that are perceivable, understandable, and don’t necessarily rely on high tech.

To design forms that fit, prioritize enhancing the form’s functionality. Enhancements might use sophisticated design and technology or be straightforward yet elegant. Inclusive design shapes forms to fit people, not the other way around.

With the enclosure on the Surface Pen in the image, users can avoid discomfort in the fingertips and the thenar web space—the area between the thumb and index finger. The mesh bubble improves the ease of gripping and lightens the pen’s weight.

Building off our inclusive design principles

Inclusive design also involves understanding the diversity of human experiences and creating solutions that can benefit many people in different ways. As we reiterate on new hardware designs, we continue to employ our inclusive principles, which have guided the development of devices to reflect our customers’ lived experiences.

Our work builds on the foundation of the Microsoft Inclusive Design principles: recognize exclusion, learn from diversity, and solve for one, extend to many. You can learn about these on our inclusive design site, but let’s put them in context of the development of the Xbox Adaptive Controller.

Recognize exclusion—We had to recognize that our standard Xbox controller, which has been designed over many generations, unintentionally excluded people through its assumptions. It assumes that people have two hands to hold it, two thumbs for the thumbsticks, fluid range of motion to hit the 18 buttons on the controller, ability to reach bumpers and triggers with their index fingers, and the strength and the endurance to hold it while playing. The development of the Xbox Adaptive Controller started by recognizing that our standard controller had unintentionally excluded people by optimizing exclusively for a primary use case.

Learn from diversity—We endeavor to design with the community, not for the community. From the very earliest prototypes of the Xbox adaptive controller, we partnered with five organizations: Warfighter Engaged, SpecialEffect, Craig Hospital, the Cerebral Palsy Foundation, and AbleGamers. These stakeholders defined the vision, with us, of what the controller would be.

Solve for one, extend to many—Designing for disabled people makes better products for everyone. When it came to the Xbox Adaptive Controller, we worked with people with many types of limited mobility. Observing and synthesizing how they moved, we designed the controller to be modular, to adapt to our customers without asking customers to adapt to the controller. Synthesis is vital when the goal is to meet the needs of interrelated disability.

We developed these guidelines to get you started on designing devices that empower the disability community. In a world that’s designed against people with disabilities, there’s a lot to do, discover, and reimagine.

Our Collective Path Forward In the spirit of our toolkit, we’ve created a booklet that augments our Surface Adaptive Kit. (Download PDF). We are also launching a community to further discuss these ideas and techniques on (GitHub Discussions) where we hope we can expand on these ideas and discuss solutions to real problems. Here are some actions to prioritize as you design:

Continuously engage people with disabilities—Personal experience is never enough. Participate in and listen to disability communities. Understanding a breadth of challenges will guide your designs.

Design to one, extend to many—Products don’t exist in isolation. Consider your design within a larger ecosystem of use, including the augmentations some people will need.

Publish examples—Showcase product utility with disabled people demonstrations. Show how your product addresses interrelated needs across disabilities.

Share success stories—Amplify the voices of people who’ve found empowerment through devices, accessories, and augmentations. Their narratives can inspire others and offer insights into potential improvements.

For the hardware toolkit, please visit Devices + Accessories + Augmentations

Read more

To stay in the know with Microsoft Design, follow us on Twitter and Instagram, or join our Windows or Office Insider program. And if you are interested in working with us at Microsoft, head over to aka.ms/DesignCareers.

Making UX research insights and frameworks beautiful

Discover how one team transformed a complex UX research framework into a visually engaging artifact to make insights stick and spark alignment across teams

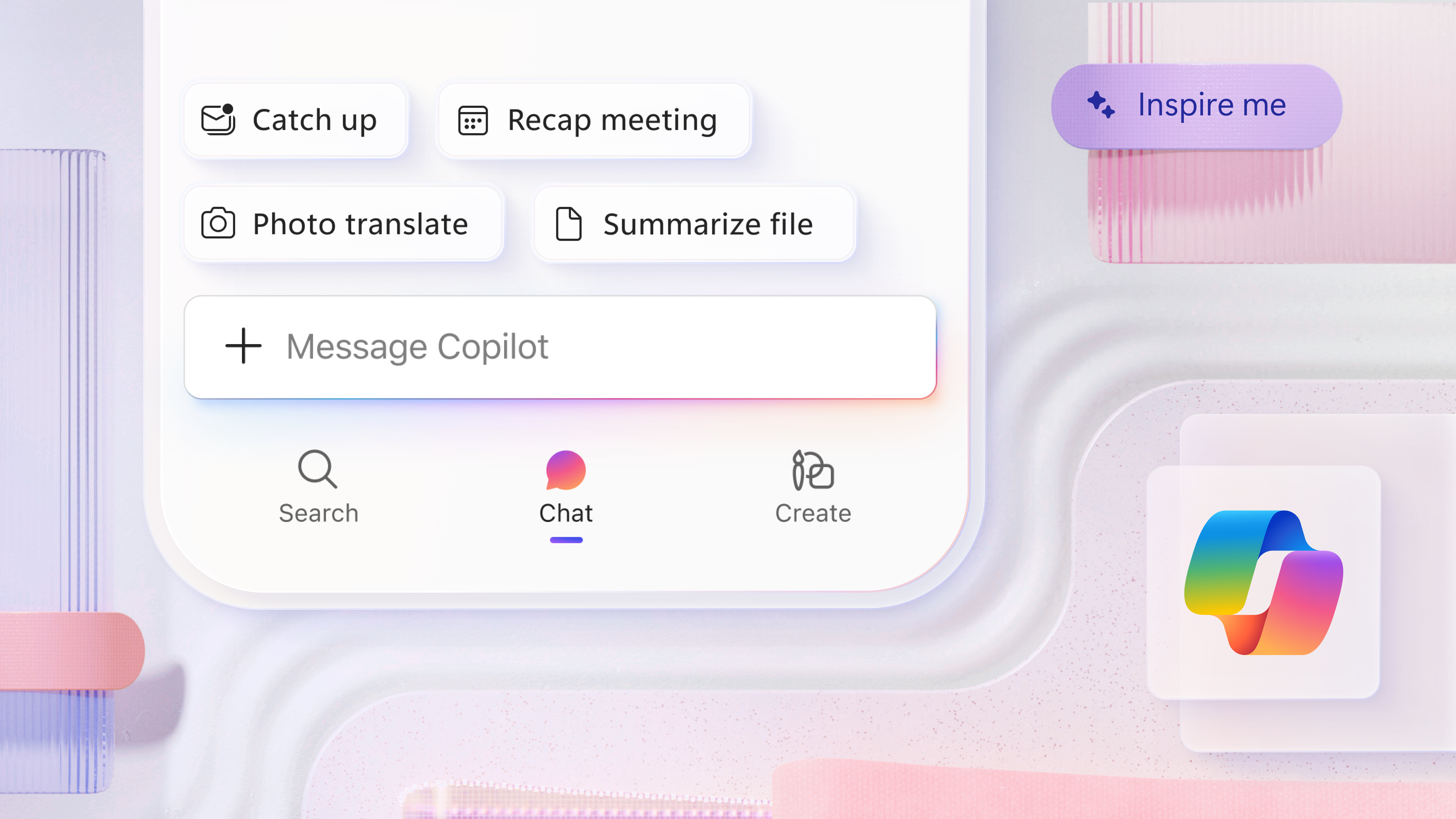

A mobile-first approach for Microsoft 365 Copilot

How Microsoft is reimagining productivity from a mobile-first lens

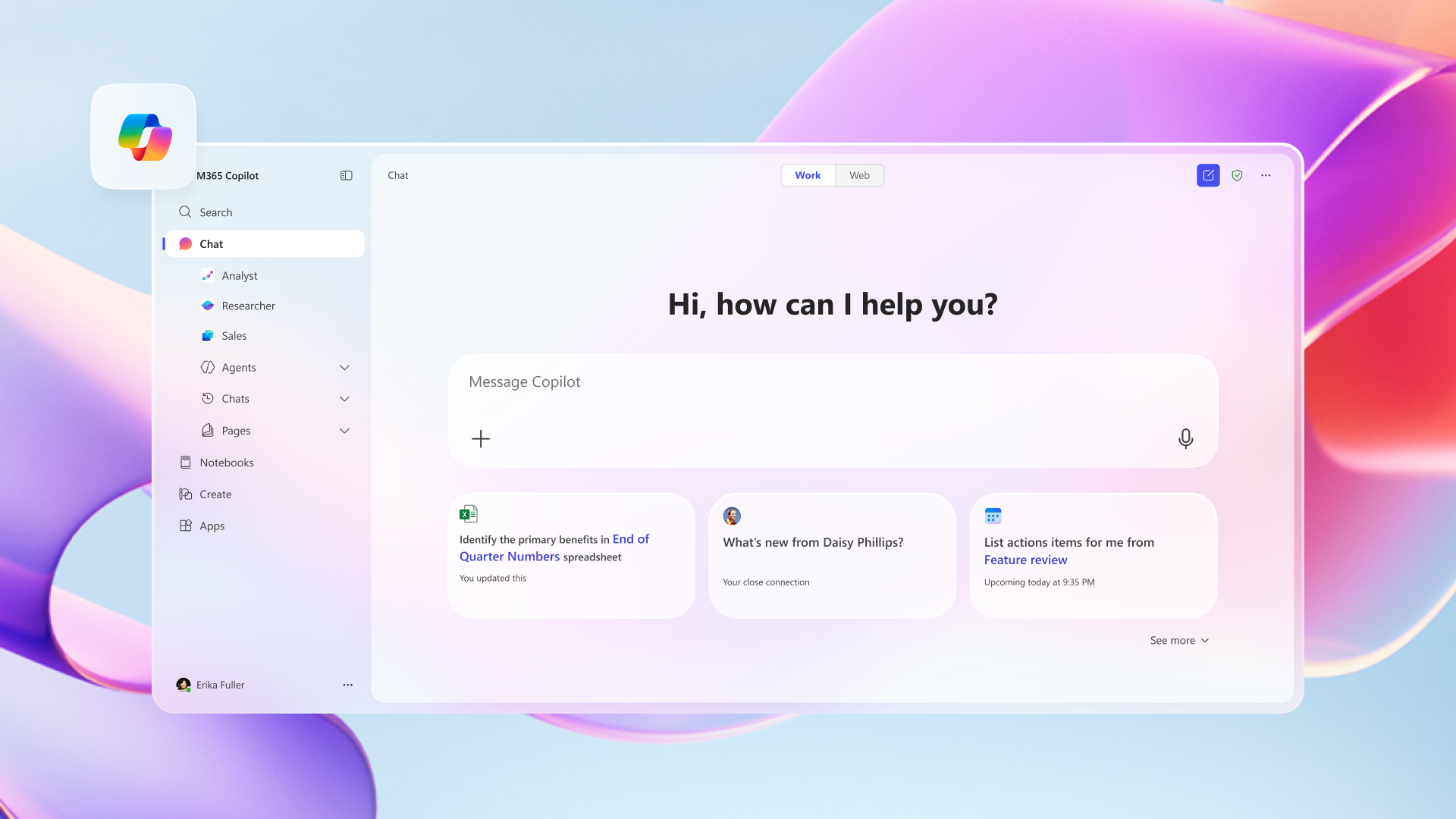

Designs for the frontier future

How we rebuilt the Microsoft 365 Copilot app for a new kind of productivity