UX design for agents

Microsoft principles and guidelines for building agentic experiences

Mark Weiser, the visionary behind ubiquitous computing, once said, “The most profound technologies are those that disappear. They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it.” In other words, good design is invisible, allowing us to accomplish tasks and achieve our goals without technology getting in the way.

As advances in AI-powered software allow us to interact with computers in new ways, good design is critical to success. At Microsoft, we have been designing and building out agentic systems, or “agents,” which are software systems that include an AI or ML model, orchestration code, and skills/tools (e.g. code writing, web search, etc.). These agents collaborate with you, automate your least favorite tasks, and scale your capabilities.

Building agentic systems comes with great challenges. Their advanced capabilities require interactions that go beyond text chat and move towards a more natural way of communicating that involves voice, vision, gestures, and more. Agents also need more data, deep user trust, and full transparency. These challenges require us to rethink existing design principles to capture new paradigms of human-computer interaction.

New principles for a new paradigm

AI agents will be immersed in our daily lives and, as with good design, should be (mostly) invisible. While still valuable, traditional UX principles do not fully address the unique challenges and opportunities presented by these ubiquitous AI-driven agents.

This is why we are excited to share with you a set of design principles specifically focused on Agent UX. Created by designers and user researchers across Microsoft, these principles provide a framework for how to think about and build individual agents and multi-agent systems. The goal of these new principles is twofold: 1) accelerate your development of agentic systems and 2) emphasize the value of human-centric principles amid rapid advancements in AI.

We leveraged deep user research and collaborations with accessibility, Responsible AI, and safety teams to ensure these principles help teams build agents that connect people, events, and actionable knowledge—while also providing appropriate transparency, control, and privacy to users.

As these systems advance, consider how your customers (particularly those outside of tech) might want to interact with technology in the future. And, of course, before you apply these principles, ensure that AI is the right tool for solving the problem at hand – plenty of customer problems do not need AI!

Terminology

Before we get into the principles, let’s define some terminology:

We define an “agent” as an AI assistant designed to execute tasks, working with or for humans. The components of an agent include instructions, knowledge, actions, skills, memory, etc. Agents may have chat experiences but generally go beyond typical chatbots.

Agentic AI systems (or “agent systems”) are made up of one or more agents. They can autonomously identify, plan, and take actions on behalf of an individual user, a group, or other agents from a general set of instructions with limited direct human supervision. An AI system may be considered “agentic” if it is autonomous, has more complex capabilities, operates in a more complex environment, and can scale to more domains.

Automation may be one aspect of an agent or agent system, but it is not required. Automation is also possible without agents, such as automatic replies in Outlook.

Agent UX Design Principles

How agents can best serve human needs

Agents mark the beginning of the next chapter in human-computer interaction. They also require a huge degree of user trust—which must be earned. We’ve worked cross-functionally to create a set of principles that guide the development of agents and ensure these systems are built in ways that serve human goals and meet human needs.

From this collaborative and research-backed effort, we identified that agents should generally do the following for users:

- Broaden and scale human capacities, e.g. brainstorming, problem solving, automation, etc.

- Fill in knowledge gaps, e.g. get me up-to-speed on knowledge domains, translation, etc.

- Facilitate and support collaboration in the ways we as individuals prefer to work with others.

- Make us better versions of ourselves, e.g., life coach/task master, upskilling, helping us learn emotional regulation and mindfulness skills, building resilience, etc.

A single agent or a single agentic system may have one, some, or all the above capabilities.

Please note that some of the capabilities discussed in the Agent UX Design Principles are under development, such as memory systems. These principles provide a forward-looking perspective to guide your team as you build out these systems.

Agent UX Design Principles

The following design principles apply to all types of agents and agentic systems. However, different agents might have different emphasis on the principles depending on their specific use cases. Use your best judgment for your scenario(s) when applying the principles.

The Agent UX Design Principles have three high-level categories with 6 sub-categories:

- Agent (Space): This is the environment in which the agent operates. These principles inform how we design agents for engaging in physical and digital worlds.

- Connecting, not collapsing: help connect people to other people, events, and actionable knowledge to enable collaboration and connection.

- Easily accessible yet occasionally invisible: an agent largely operates in the background and only nudges us when it is relevant and appropriate.

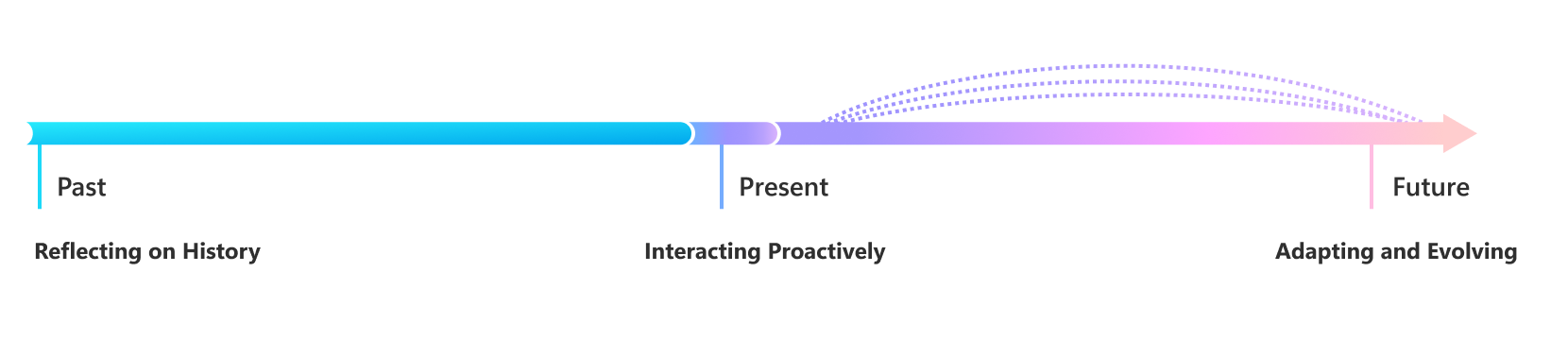

- Agent (Time): This is how the agent operates over time. These principles inform how we design agents that interact across the past, present, and future.

- Past: reflecting on history that includes both state and context.

- Now: nudging more than notifying.

- Future: adapting and evolving.

- Agent (Core): These are the key elements in the core of an agent’s design. These principles inform how we design the foundation of individual agents and how they might interact with other agents.

- Embrace uncertainty but establish trust.

- Transparency, control, and consistency are foundational elements of all agents.

More details are provided below.

Agent (Space)

The Agent (Space) principles relate to the physical and digital environment in which the agent operates.

Connecting not collapsing

- Agents and agentic systems help connect events, knowledge, and people. Agents bring people closer together.

- Agents are not designed to replace or belittle people.

Easily accessible yet largely invisible

- Individual agents and multi-agent systems are easily discoverable, intuitive, and accessible for authorized users on any device or platform.

- Any human-facing agent supports multimodal inputs and outputs, such as sound, voice, text, images, etc. Active multimodal capabilities are clearly visible to the user.

- Agents may seamlessly transition between foreground and background, e.g. operating invisibly as a background process.

- Agents may also transition between proactive and reactive, depending on:

- User needs, e.g. ‘Do Not Disturb’ setting results in little or no engagement;

- The types of actions the agent takes, e.g. an action requiring user feedback results in proactive engagement with the user; and

- The tasks the agent is working on, e.g. important tasks may result in proactive engagement with the user.

- An agent may run as a background process, unnoticed by or invisible to the user. However, the actions an agent takes, including collaboration with other people or agents, are visible and controllable by the user via dashboards, settings, or other log type UX.

Agent (Time)

The Agent (Time) principle relates to how an agent operates over time.1 These principles inform how we design agents that interact across the past, present, and future with other agents, primary users, or other humans.

Reflecting upon history beyond states only (from past to now)

- An agent uses data in memory to inform and engage with current events and tasks. This includes creating connections from past events, actions, tasks, and user queries.

- Agents use memory and connected databases to provide more relevant results based on analysis of richer historical data beyond singular events, user queries, or states.

Nudging more than notifying (around “now”)

- An agent embodies a comprehensive approach to interacting with people. When an event happens, an agent goes beyond static notification or other static formality, e.g. it may proactively start a chat or create artifacts. Agents can simplify flows or dynamically generate cues to direct the user’s attention at the right moment.

- Agents deliver information based on contextual environment, social and cultural information (e.g. private vs. public location), and user preferences.

- Agent interaction can be gradual, evolving and growing in complexity to empower users over the long term.

Adapting and evolving (from now to future)

- An agent runs on and adapts to various devices, platforms, and modalities. For example, based on user preference, an agent may default to a voice-first interaction on mobile but text-first interaction on a PC.

- An agent adapts to user behavior and feedback, accessibility needs, and customization.

- An agent is shaped by and evolves through continuous user interaction.

Agent (Core)

These are the high-level elements to consider in the core of an individual agent’s design for both human-facing and foreground agents, as well as agents that run as background processes.

Embrace uncertainty but establish appropriate trust

- A certain level of Agent uncertainty is expected. Uncertainty is a key element of agent design.

- The level of certainty and reasoning behind a recommendation are visible and/or easily accessible to the user to avoid overreliance.

Transparency, control, and consistency are foundational elements of all agents

- Agents’ associated knowledge, tools/skills, and connections with people and other agents are transparent and customizable. This helps build trust with users.

- Agents that operate as background processes have a user-facing mechanism to view and control actions and automations.

- Humans can customize agent settings, including specifying preferences and personalization, and are in control of when the Agent is on/off.

- Agent status, or what the agent is doing, is clearly visible at all times.

- Agents use familiar UI/UX elements where possible (e.g. microphone icon for voice interaction) and reduce the users’ cognitive load as much as possible (e.g. concise responses, visual aids, and ‘Learn More’ content).

Looking Ahead

These Agent UX Design Principles are a starting point for designing new types of user experience with digital devices. As agentic systems continue to evolve, we need to continuously reflect on what works well and refine our approaches and solutions.

As with any product development process, it is critical to start with an end-user/customer problem and then brainstorm possible solutions that may or may not involve the use of AI. This helps to ensure we continue to center human needs as we create new user experiences with agentic systems.

Ultimately, in taking this human-centric approach, we can enable every person on the planet to achieve more, solve bigger and more complex problems, and collaborate more effectively with people and computers alike.

Primary Contributors: Ruokan He, Jen Fox, Amanda Snellinger

Additional Contributors: Inclusive Design team, Office of Responsible AI team, Angela Argentati, Aamir Jawaid, Courtney Khalil, Dan Littlewood, Don Diekneite, Jennifer Wang, Joey Glocke, Martin Danty, Ming-Li Chai, Rachel Romano, Richard Banks, Ruth Kikin-Gil, Saleema Amershi, Sid Uppal, and Sunder Srinivasan.

Read more

To stay in the know with Microsoft Design, follow us on Twitter and Instagram, or join our Windows or Office Insider program. And if you are interested in working with us at Microsoft, head over to aka.ms/DesignCareers.

When AI joins the team: Three principles for responsible agent design

A practical guide to build agents that stay differentiated, intent-aligned, and bias-resistant

The new Microsoft 365 Copilot mobile experience

How we redesigned the Microsoft 365 Copilot mobile app to create a workspace built around conversation, dialogue, and discovery.

The new UI for enterprise AI

Evolving business apps and agents through form and function