Raised by an afrofuturist

The first in a series of personal essays that brings to life the rich perspectives of the design community at Microsoft

Editor’s Note: This is part of a series of personal essays that bring to life the rich perspectives of the designers, storytellers, UX engineers, researchers, and operational leaders of Microsoft Design. We hope it helps product makers move beyond personas, expanding notions of individual identity, what diversity means, and how to design for a fuller range of human experiences.

When I was a kid, I wrote poems to steal rings from Saturn and place them around the moon. Arranging words like code conjured coal miners digging wormholes in the bones of otherworldly flowers. Poems were prayers, spells, inter-dimensional escape routes, weaponized metaphors against the country that my folks knew, but would not speak of.

Invention’s mother are plumbs of color

exploding out of the darkness

Like slaves freestyling Biblical verses

to see whose God is closer,

they prearrange their heavenly spot,

knowing their story’s arc

lives outside the lines of Willie’s plot

That pulsar

that Burnell discovered

was just one of the many styles we rock

— back when you was

lying about Vietnam

and all those bombs you dropped

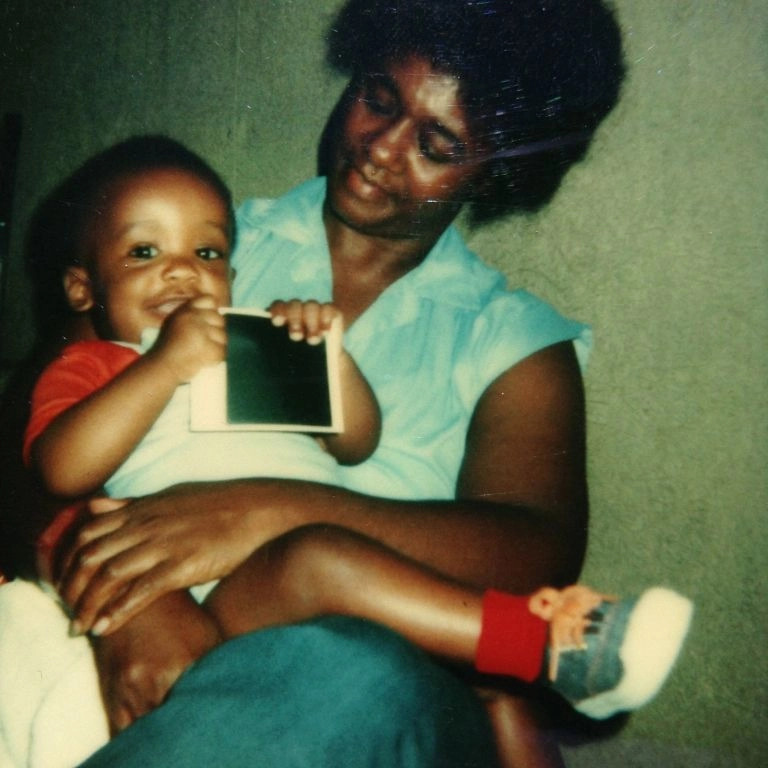

Like most Black mothers, my mom was an Afrofuturist before the term existed. From a design perspective, Afrofuturism is about inventing technologies that aid Black freedom. It’s about materializing beautiful dreams inspired by living nightmares, mobilizing the people, revolution. It’s the thing that sustained my mother’s unrelenting hope.

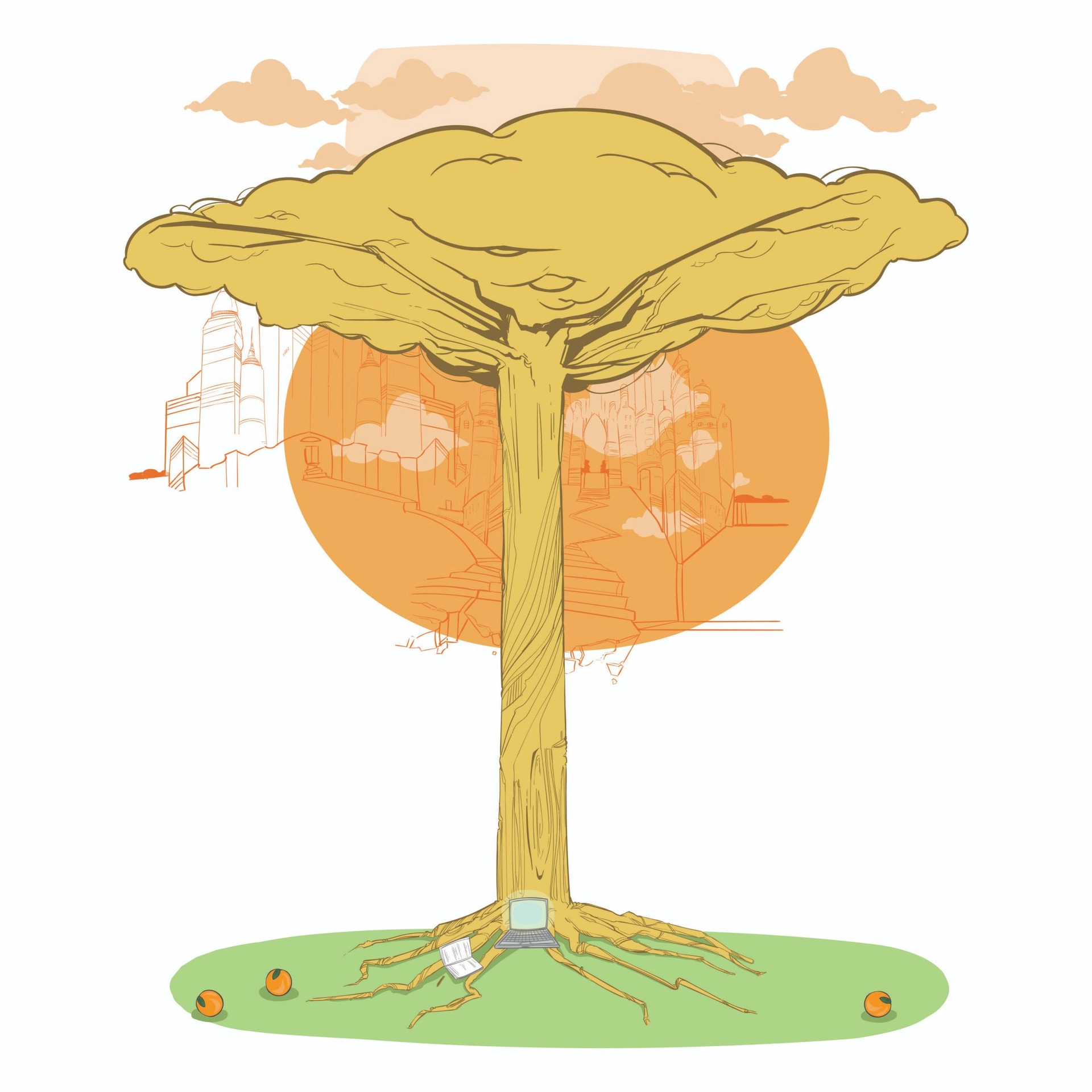

She grew up on a plantation, a corporate orange grove in Tampa, Florida. She belonged to a family of migrant workers that picked oranges, tomatoes, and cotton. My mother, born in 1942, was the last of 17 children. She lived in a one-room shack with a dirt floor and she wanted to be a writer.

She was a fan of cornball romance novels. “One day…,” she’d say when starting to dream out loud. “I’m going to write a book.” She beamed as if speaking her vision into existence. “Why you always talking about ‘one day?’” I would say. I didn’t know that this was a woman whose father witnessed The KKK lynch my great granddaddy. This was a woman whose mother was raped by five white men.

Patient as ever, my mother pat her youngest son on the cheek, “Well, you’ll see. One day at a time, pumpkin,” she said. Throughout her life, she would time travel. Wielding a fiery sword, she would fight off her mother’s attackers. To save my great granddaddy, she aimed a shining silver ray gun and charged grand dragons while surfing the air on a hoover board. In the future, she wrote a bestseller that when read, summoned clouds to rain money on the hood.

Though I flunked kindergarten at my predominantly white elementary school, and I was told that I have a slow learning disability, I always wanted to be like her. She passed away before she could see what I became on that “one day.” Maybe she already knew. Despite us living for long stretches without lights, water, or phone, she predicted that my college education would get paid for. Afrofuturists always imagine the impossible.

Writer Mark Dery coined the term in his 1994 essay, “Black to the Future.” He described our plight as a sci-fi nightmare, referring to us as “alien abductees.” Back then, he asked, “Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures?”

28 years later (minus a zombie apocalypse), amid search engines labeling us gorillas, bad facial recognition endangering Black bodies, and biased algorithms automating discrimination, what would those “possible futures” look like?

From the basement of a Bedstuy, Brooklyn project, Cornbread and Pooh run fire on computers. Ever since their father was kidnapped, Cornbread got into hacking. Pooh followed her big brother’s lead. Their countless failed attempts to do what’s never been done is about to pay off.

One of them taps the return button. They bolt out of the basement. This will be their “one day.” Metal doors fling open. Across the United States, out step hundreds of thousands of young Black men and women who over represent the prison population.

They organize and motivate to eradicate predatory bail, unjust drug laws, and capital punishment. Legions of them flood the streets. Lasers shoot from their gas masks to distract cops and render surveillance cameras useless. Runaway robots who were enslaved join forces. Sympathetic autonomous drones do reconnaissance.

Ex-drug dealers and gang members, male and female, make the flyest jewelry that secretly records police interactions and disrupts radio signals and cellphone towers. These artists and scientists, friends of Cornbread and Pooh, create rollie chains equipped with thousands of nano cameras. Using biometrics, these miniature eyes detect staff that monitor and follow Black shoppers around stores. When the chain identifies overseers, the voice of an angry white lady shouts, “Do I look like a thief?”

White Collar Crime Early Warning System has become the most downloaded app in the world. It predicts bad neighborhoods with the highest risk of financial crime. Like a Chappelle Show skit, CEO’s are treated like drug dealers. Suits are thrown against the hot hoods of police cars, patted down, handcuffed, and hauled off to jail.

In droves, kids, babies, mothers, and fathers walk out of immigrant detention centers. Jails, rows of hard drives, racist statues, and detention centers erupt, spouting rainbow sparks in every direction. On street corners, crowds of Black men converge for group hugs. “I love you” can be heard amongst them. Black women, after giving birth to civilization and enduring the worst of the patriarchy, prepare to lead a world absent of borders or governments.

Cornbread and Pooh, along with many others, had been coding against the matrix, unleashing weapons of mass emancipation, eroding caste systems, and corrupting all forms of government surveillance. As they raced toward the subway, thrilled, terrified, and joyful, it was as if they were traveling to the past and the future at the same time.

Kids like them don’t use buzzwords or brands to describe design. They are the untouchables. Get free or die trying is the code. Their algorithms calculate ways of crawling out of a lion’s mouth. Though everything is design. They are oblivious to design-speak, design-thinking, but life has taught them that people are weird, violent, irrational, compassionate, beautiful and complicated. “An app will not save us. We have to save ourselves,” scholar Safiya Noble proclaimed.

In Ruha Benjamin’s Race after Technology, she thinks that “design is a colonizing project” since it’s meant to express a value system, maintain power, and visually shape something. In a “subversive design” workshop she took, the class was asked to think critically about the assumptions of design and that of justice. She said:

If, in the language of the workshop, one needs to “subvert” design, this implies that a dominant framework of design reigns — and I think that one of the reasons why it reigns is that it has managed to fold anything and everything under its agile wings.

Benjamin proposes that designers should be accountable for their inventions and the effects that they have on the world. Former Microsoft designer Ovetta Sampson put it like this, “Once your model is released into the world, you’re not the only one training it.” She describes the building of a “mindful A.I.” by a collection of people who represent all hues, religions, special needs, gender, nonbinary, trans, and sexual orientation.

If design gives order to chaos, Benjamin states that there needs to be “socially just imaginaries,” interdisciplinary acumen, and a redefining of design. The basis of all of this is to tell our stories. Narrative navigates our conscious to live beyond default settings, to innovate minus speed and competition. Solidarity through interdependence won’t create hierarchical allies, but co-liberation.

Cornbread and Pooh thread the sea of orange jump suits leaving Rikers Island prison. A voice, surprised to see two kids, yells, “Hey, whatchaw doing out here?” Pooh continues to run while turning to answer the voice, “We’re looking for….” Her head bounces off of a man’s hardened stomach that used to be soft and round as if pregnant. He used to have black hair, but it’s turned grey, along with his white wooly beard. She hadn’t seen him since she was 9. Pooh is 13 now. She looks up, “Dad!” Cornbread, 16, collides into them with a hug. Their father, tears streaming. As he wraps his long muscular arms around them, he searches their faces, looking for familiar features from when he last saw them.

Kids reuniting with their fathers blossom all around. “Did you do this?” Cornbread and Pooh’s father asked. “Let’s go home, Dad,” said Cornbread. Their Dad smiles, shacking his head. “Ya momma gonna getcha.”

Just as you are the fantastical aspirations of your family, I am the impossible that my mother imagined, and we are the living dreams of our ancestors.