Power of the Pluriverse

How principles of radical interdependence can be applied to UX design

An African proverb popularized by the late author Chinua Achebe goes, “Until lions have their own historian, the story of the hunt will glorify the hunter.” — We are the lions’ historians when we listen to the often ignored and amplify the narratives of the often excluded. These narratives form the threads of our collective journey, causing us to seek new ways to live together because one perspective is never enough to understand the full story.

Product teams often express a desire to craft products that serve human needs. But given that hundreds of parallel worlds and realities exist across this planet we call home, meeting those needs means considering multiple perspectives, — something few design tools or tenets currently take into consideration. We must expand our thinking, find new ways to engage with our world, and celebrate the rights of others to coexist in a world where many worlds fit.

Rooted in this charge is the idea — and power — of the pluriverse. Greta Gaard, a professor and author of Critical Ecofeminism, defines the pluriverse as “a world in which diverse hopes can be sown, multiple opportunities can be cultivated, and a plurality of meaningful lives can be achieved by the richly different and caring people we are.”

To help put that philosophy into practice, I have laid out a set of principles which will enable UX researchers and product makers to adopt a pluriversal lens. These principles emerged from my academic research and continue to evolve through collaborative work with design students, UX designers, and most recently peers at Microsoft XC Research.

Whose futures are we omitting?

Before exploring the principles themselves, let’s consider what’s at stake. Historically, product design has focused on white, Western perspectives rather than designing in a way that recognizes, celebrates, and amplifies a multiplicity of lived experiences. The reasons for this vary — from colonial legacies, time, budget constraints, to lack of representation. What is consistent is the risk we run of carelessly proposing a very narrow view of the future that stifles innovation and increases inequity.

In today’s market, we see this often with the vast majority of software being geared toward users with stable internet access. This excludes people on the other side of the digital divide — individuals requiring more offline experiences, families sharing a single device, or communities relying on mobile-first experiences. For many people, it comes down to what they can afford or what is available to purchase.

But what would it take to design products for those historically excluded? How might we consider creating software products that assist people with disabilities, or those who might be economically disadvantaged? This mode of inquiry forces us to acknowledge what Anne-Marie Willis calls ontological designing, or that “we design our world, while our world acts back on us and designs us.” This phenomenon forces us to acknowledge the power of the pluriverse. By creating a future that omits the lived experiences of others, we lose all the beautiful things that make us human. What and how we are designing begins to destroy our collective livelihood.

And finally, there’s this: innovation is usually found in the most unlikely places. There’s a reason that the hare running for its life generally outruns the fox running for its supper. When it comes to AI and new ways to collaborate, the most valuable and creative solution to your current problem may come from a place or a people that you have yet to encounter. So, how do we stay humble and begin accounting for this multiplicity within the confines of our singular reality?

Pluriversal Principles

Designs for the pluriverse allow us to use design tools, processes and frameworks to critique and improve the discipline.

Connect all diverse perspectives: We must commit to identifying, examining, and dismantling all impacts of internalized oppression biases and privilege in our work. Recently, for example, our research teams have been actively engaged in understanding the lived experiences of customers on the other side of the digital divide. These insights help inform product teams — with no experience living with low or no internet — how to create better free software experiences.

Elevate excluded voices: We must work to deemphasize dominant perspectives and continually strive to elevate stories of the historically excluded. That means refocusing design from its Western colonial influences and recentering it to address new and emergent approaches drawn from multiple influences. Microsoft’s Inclusive Research team — which rejects binary approaches to UX research and engages a multiplicity of lived experiences — details this process in When Equal Isn’t Equitable. They partnered with a nonprofit network to disrupt the system of traditional customer feedback channels. The catch-22 — marginalized voices tend to live beyond the systems in which product design is constructed from. Now, as a result, product makers have regular pathways to meaningfully connect with racial and ethnic minority communities, as well as people with disabilities, lower incomes, unreliable internet, mobile-only access, non-English speakers, and more.

Micro-interventions matter: The smallest contributions can cause big shifts, so be prepared to engage at any level. We need to make space for more forms of contribution by empowering everybody to design, including communities historically excluded from the design process. This mode of working means that the designer is no longer the “white knight” who rides in to “solve” every problem while ignoring the consequences. Instead, the designer actively engages the community of stakeholders in addressing their unique challenges. At Microsoft, there is an effort underway (in the Microsoft 365 UX space) to bring co-design into everyday practice. UX designers are actively working with participants to leverage their influence on the products that they use.

Be aware and intentional: Always lead with compassion, understanding who is included, excluded, and the impact of that. Amassing that understanding often means looking beyond the immediate. For centuries, Indigenous cultures worldwide have considered our collective journeys not just intertwined but also representative of a constant negotiation between our past, present, and future. In Ghana, for example, the Adinkra symbol Sankofa, often represented by a bird with its head twisted to look behind, can be loosely translated to mean “it is not taboo to fetch what is at risk of being left behind.” In other words, we cannot fully understand where we are going until we know from where we have come.

Be human: Every problem is a human problem. Commit to humanity. Be compassionate. We need to confront our assumptions on diversity, or even inclusion, and reframe them around sustaining our collective livelihood — one that protects the right of others to exist in the future we are making together. This kind of posture will require us to think differently about what we are making and the effects they have on our world.

Design with honesty: Don’t mask inconsistencies — face them head-on and use design to reveal truths. With advances in Artificial Intelligence and other emerging technologies, we have a unique responsibility to approach our work with humility and to prioritize collective benefit over short-term profits. Designing with honesty means actively avoiding deceptive practices (such as dark patterns in UX) that manipulate users to do things that are potentially damaging to them.

Stay with the problem: Riffing from Donna Haraway’s notion of “staying with the trouble” — have a long-term commitment to the problem space. Stay the course. This means becoming comfortable with discomfort, including when it applies to our own discipline. For years, we have only accepted Western understandings of design as valid and this remains a comfortable space for many (to the point that many folks aren’t even aware of this bias; it’s simply the water the industry swims in). A shift to the pluriverse asks us to recalibrate our relationship to design; we will need to evolve our approach to its teaching, practice, and overall orientation, all of which require long-term commitment in service of the best possible outcome.

Living our ancestors’ dreams

Our imperative is to shift the paradigm from UX as a human-centered (or universal) venture to one that expands to reflect humanity and other-centered (pluriversal) design practices. Pluriversal UX orients toward enhancing our collective livelihood through radical interdependence. This means that our focus must be to empower our customers and stakeholders by creating objects or systems that emancipate as opposed to weapons of oppression. Transcending the status quo in UX means that we must redesign the practice to bring in new voices, different histories, and new perspectives. As the Yoruba Proverb goes, “The sky is not seen from only one single spot.” In other words, there are many ways to achieve a goal: don’t be fixated on one.

Special thanks to Rachel Romano, Tracy Jones, Wicksell Metellus, Jabe Bloom, Char Popp, Adoley Adu, Katie Derthick, Vicki Lim, Mariam Mayanja, Ilana Krause, Kelsey Vaughn, and students at Emily Carr University in Vancouver BC and ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena for their contributions to these ideas.

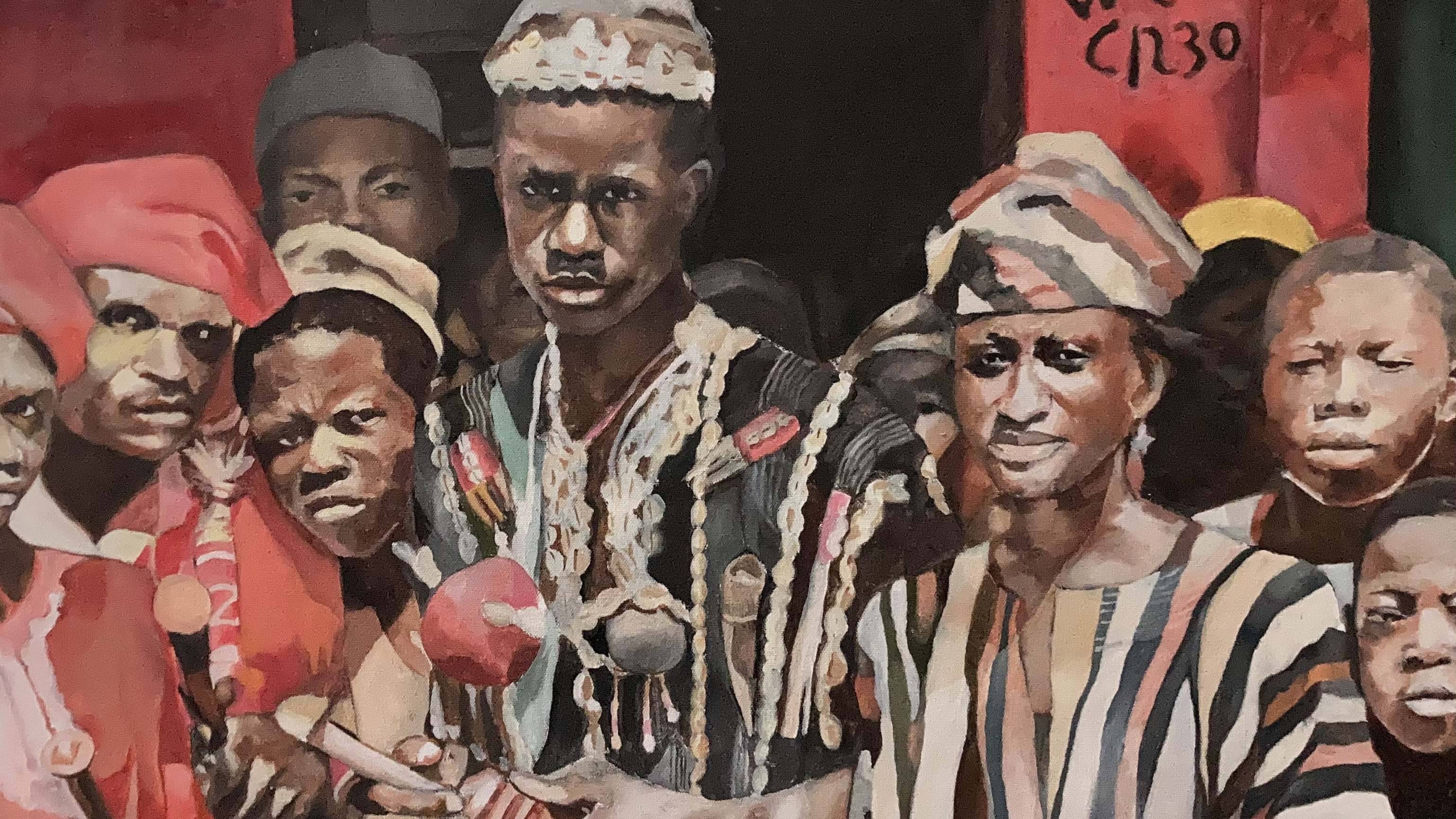

Painting titles in order of appearance: Story of a Young Woman, Outside, Looking In, The Story About a Little Girl with the World at Her Fingertips, Transition (My Ancestor’s Dream).