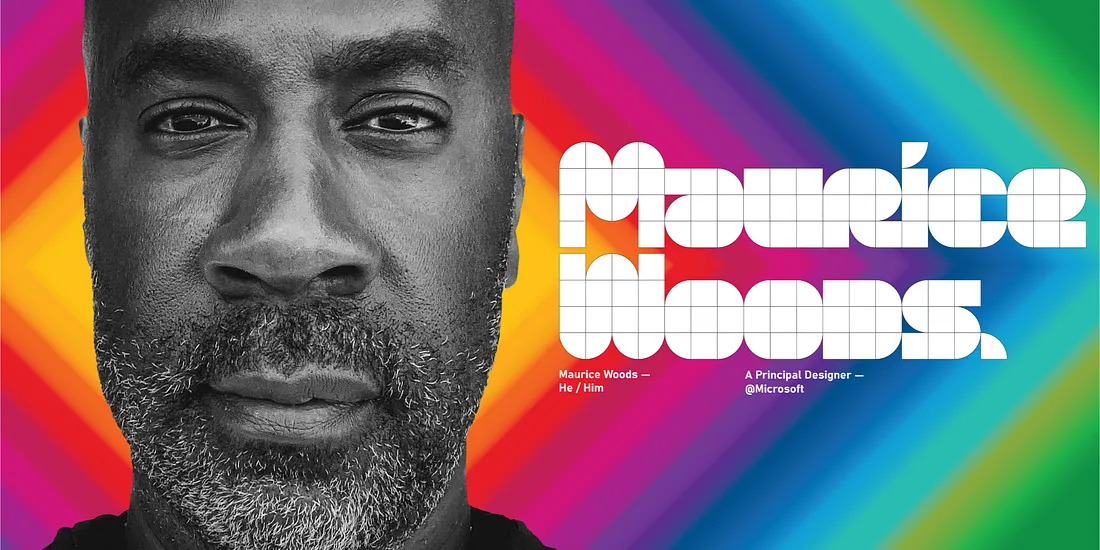

Maurice Woods: Changing the world through design

How a Microsoft designer uses activism to bring the Black experience to the forefront at work and beyond.

Can you design for a community with whom you have no connection to? “Yes,” says Microsoft Principal Designer Maurice Woods. “But the connection to that culture and the ability to feel the nuances of that culture, they can’t.” Well, what are those nuances and why won’t non-Black designers ever understand them? Does it even matter?

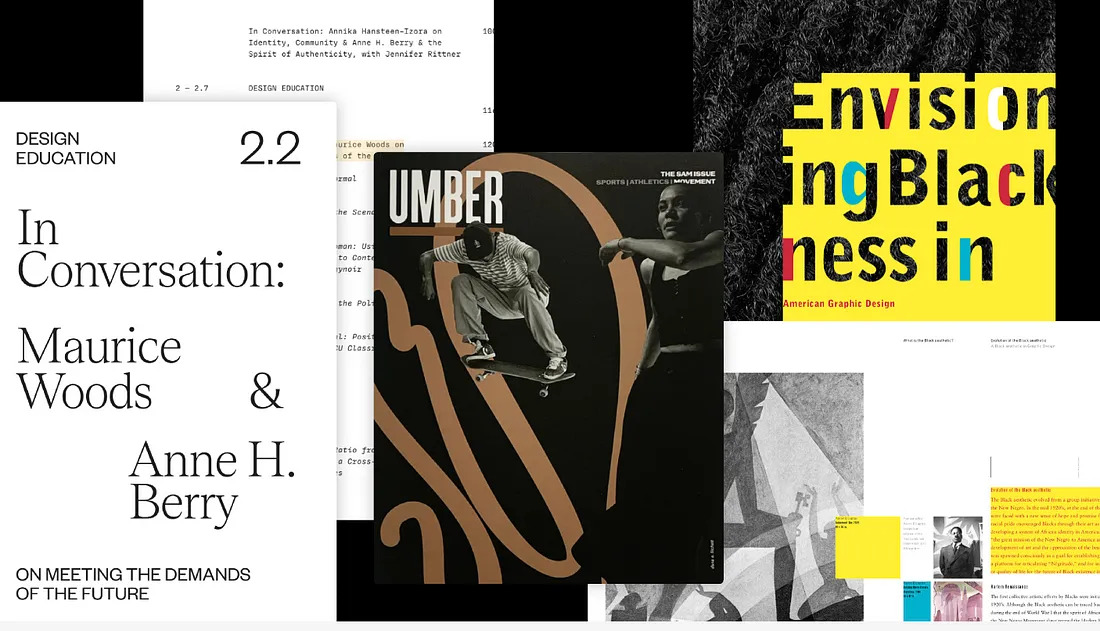

Almost seven years ago, Woods started working at Microsoft’s newly acquired company, MileIQ, a consumer product app that tracks your business and personal mileage. He would lead design for the minimal viable product version of the Microsoft Family Safety mobile app, and he would orchestrate multiple Educational UI and UX projects. Woods has been routinely featured as a keynote speaker and a leading voice for Black and Brown aspiring designers. At Microsoft, he leads multiple design teams in education, prototyping, illustrating, animating, and engineering. Prior to this article, I had briefly heard of Woods through a colleague, but it wouldn’t be until I read The Black Experience in Design: Identity Expression & Reflection that I would discover the edge of his cratered impact, which got me curious, who is this guy?

“I feel like I’ve had multiple careers in my life,” Woods said. Before Microsoft, he worked for the world-renowned agency Pentagram Design Studio. He designed for Nike, Greyhound, and Priceline, he was a lead designer at another major tech company, and he’s a Jefferson Award recipient. Yet how he got to Microsoft wasn’t at all a linear path. Prior to becoming a designer, Woods had hoop dreams.

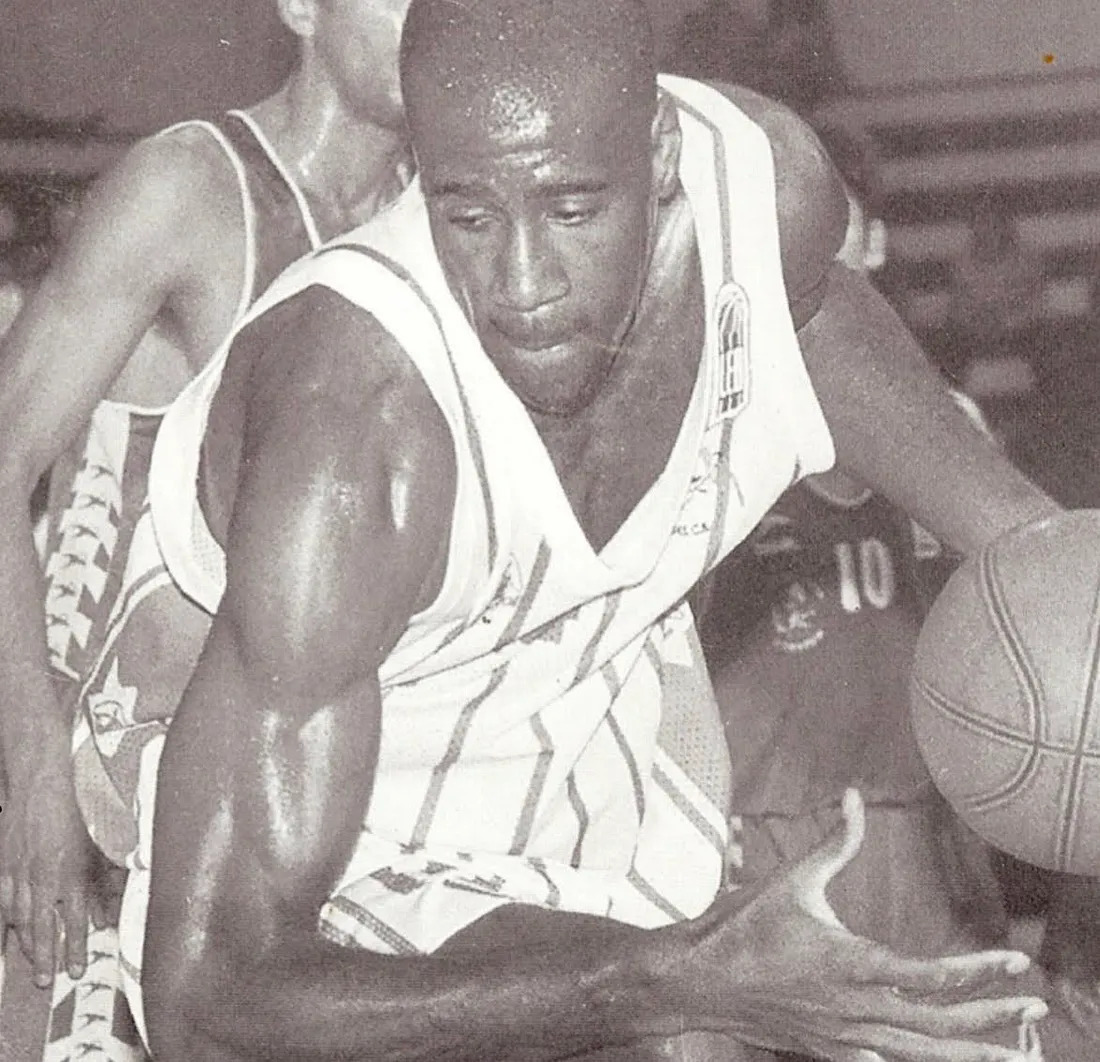

At the University of Washington, he was on a basketball scholarship. Balling was life until his sophomore year when the time came to declare a major. “What are you going to do?” could’ve been silently written in clouds, but the question was loud all the same. “I just started taking classes. I didn’t know what I wanted to do.” He randomly dropped into a graphic design class that would leave an everlasting impression on him. “Back then, I didn’t know what design was,” he said

Post undergrad, Woods bounced to Europe where, as a professional basketball player, he was breaking ankles and hitting water. Seven years later he would come back home to the U.S., go to graduate school, and study design. This time the class was familiar. He was assigned to write a thesis paper on how he would use design to change the world. Writing that paper would profoundly change his life, leading him to later change the lives of countless others.

“I took the assignment literally,” he said. Woods came up with the idea of teaching kids design. “While I was in Seattle, I was coaching basketball, so I knew all the community centers,” he said. Promoting his design class was a great excuse for him to design posters. “I was literally going to community centers and just handing out flyers, giving things out to parents, putting up posters,” he said. A lot of community centers, including those with Black community members, didn’t want Woods teaching their kids design, but eventually he found a center that gave him space to teach.

It was the beginning of summer and with no curriculum or formal training, Woods started with three students. “By the end of summer, I was working with 30,” he said. According to Woods, in the Black community, success is a doctor or a lawyer. Wealthy white parents tell their kids to dream their biggest dream, go out into the world, make that dream a reality. Black parents tell their kids to get an education and find a secure job. “We’ve been under systems of oppression for hundreds and hundreds of years,” said Woods. And still, like an escape route from places where dreams are deferred, where role models are street corner hustlers that make more money selling drugs than doctors do seeing patients, a lot of black youth aspire to play professional ball on TV. “Less than 2% of basketball players will make it to the NBA. You got hundreds of thousands of Black kids trying to make it. Now, if I was to tell you, ‘Ok, I know you want to do this job, but you have less than a 2% chance of doing it. Would you put all your eggs into that basket?’” said Woods.

They work within a discipline that supposedly has no Black legacy, and where the majority of things that we use in our everyday lives are mostly designed from a white perspective.

The chances of becoming the next LeBron James may be slim, but basketball players, just like rappers, and entertainers, have created a Black legacy within those fields. Woods is among the 4.9% of Black designers that have to navigate through white spaces. They work within a discipline that supposedly has no Black legacy, and where the majority of things that we use in our everyday lives are mostly designed from a white perspective. On a broader scale, the omnipresence of design shapes our life experiences in ways that we are not aware of. Great design is often described as invisible, but Woods saw its power. For centuries, design has been a Black practice without a name. In recent history they were crafting handmade quilts out of discarded fabric and putting them in front yards of abolitionist to mark subway stops along the underground railroad. Woods’s quilt would be passing his knowledge of design to liberate young minds.

His thesis paper about using design to change the world would turn him into the founder of Inneract Project, a nonprofit program that, for 18 years, has been a support system for teaching middle and high school kids about design. The program informs youth of practical pathways to having a feasible career in the world of design. Thus far, almost 3,000 middle and high school kids have gone through the program, which is a catalyst for future designers. As of recent, Inneract has started Uplift, an online platform where underrepresented designers can get mentorship and a host other support to aid in their career. Similar to Woods at Microsoft, they’ll design things that make people’s lives better. For Woods, to be a designer is a privilege. “If we’re designing stuff for 50 million people, you damn better believe that there’s gonna be some Black people that we’re designing for and their perspective is going to be in there. Latin folks, they gonna be in there. I feel like that’s my responsibility as a designer,” he said.

When Woods was asked about the absence of a Black legacy in design, he said, “I believe that African American culture is a predominant aesthetic in American culture. And I have issues with it because a lot of our stuff gets stolen. When we look at the things of this world and we look at the designs and everything, our African American culture is all in there,” but it’s seen through a white filter.

Designing with the pure intention of enriching the Black community would mean that designers have to know about seeing a hot comb laying on the red eye of a stove. The sight signaling your mother going out, your auntie on her way over to get her did. The smell of burnt hair in the air. Gossip, laughter, and a lot of Black America’s problems would be laid to bare. As a kid of one of those Black women, you are getting an impromptu education about life, but as a designer you would never be short of having problems to solve, which is why nuance matters and why we need more Black designers. Woods said, “I think our country has a long, long way towards building products and services that are diverse for all. Designers have to be mindful of the fact that the decisions that you’re making in your design affect people, not just your people, but all people.”